Introduction

The World Bank Group (WBG) and International Monetary Fund (IMF), also known as the “Bretton Woods institutions,” are global financial power brokers dominated by US and EU interests. Their prominent role in the multilateral, public financing landscape reflects their origins and goals following World War II to build a new, stable, global order in the interests of the Allied Powers. However, their existing structures limit their effectiveness in addressing present-day challenges, notably in assisting heavily-indebted, climate-vulnerable countries mitigate and adapt to the climate crisis.

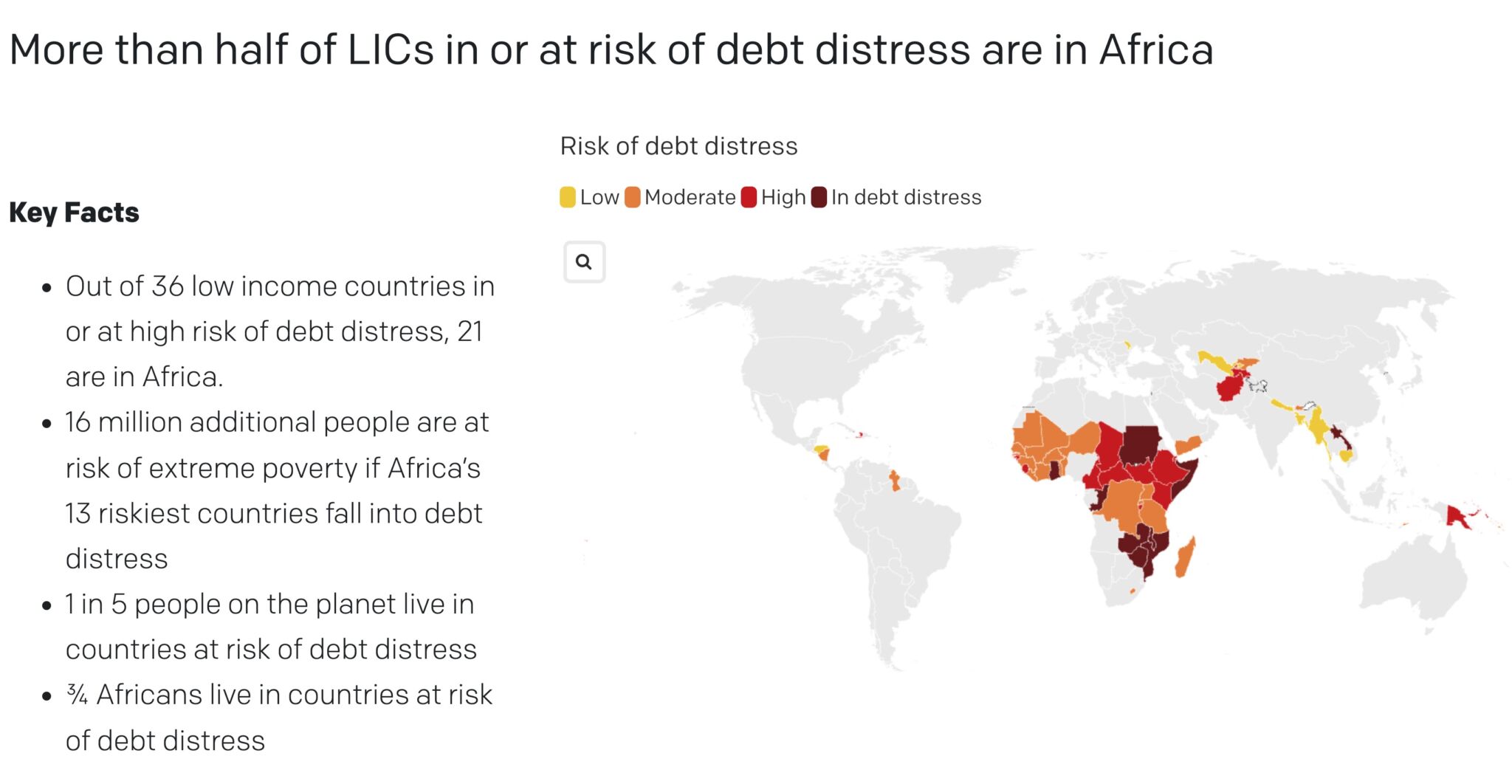

A staggering ninety-three percent of countries most vulnerable to the climate crisis are in debt distress or at significant risk of it. The annual climate financing needs for emerging markets and developing countries (other than China) are projected to reach $2.4 trillion by 2030, highlighting the connection between debt and climate resilience.

Background

Though often discussed in tandem, the Bretton Woods institutions have distinctly different mandates. The IMF aims to “promote global macroeconomic and financial stability.” For debt-distressed countries, this often involves seeking emergency “last resort” loans to avoid debt default. To qualify, countries must adopt an IMF “program” – a series of measures designed to minimize government spending. While they do help stabilize the global economy, these programs have received criticism for their adverse effects on the poorest and most vulnerable populations, while failing to lift countries out of debt long-term.

The World Bank, on the other hand, aims to “promote long-term economic development and poverty reduction.” It does so through three lending windows:

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD): Offers non-concessional loans and loan guarantees to middle-income countries.

- International Development Association (IDA): Provides concessional loans and grants to low-income countries.

- Concessional loans have better terms than market rates. Due to their “risk”, lower-income countries often have interest rates 3-5x higher than higher-income countries and therefore rely on IDA finance to complete large-scale projects. Unfortunately, many of the most climate-vulnerable, small island developing countries do not qualify due to their GNIs..

- International Finance Corporation (IFC): Offers non-concessional loans, equity investments, and loan guarantees to private-sector firms in middle- and low-income countries.

As the largest multilateral funder of climate finance in developing countries, the World Bank primarily offers debt-creating finance options. While the IMF has operationalized a Resilience and Sustainability Fund to provide longer-term loans to address climate risks, so far this has amounted to less than $5 billion in approved projects. Otherwise, the IMF provides fiscal support to heavily indebted nations and controls “Special Drawing Rights” (SDRs), a reserve asset exchangeable for currency and used in the past to boost liquidity during emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Since SDRs are allocated based on IMF shares, developing nations have asked for unused SDRs to be rechanneled from high-income to low-income countries, as well as for a more equitable allocation of additional SDRs.

Many climate-vulnerable countries cannot afford to take on additional debt. A recent UN report cautioned that we may be in “a vicious cycle of perpetual vulnerabilities and economic stagnation” for indebted economies on the front lines of climate change.

Countries at risk or in debt distress, source: DataOne & IMF Debt Sustainability Analysis

Framework Solutions

Several initiatives have emerged to address these issues. The Bridgetown Agenda, a climate and development plan proposed by Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley, aims to reform the global financial system, delivering vital financial resources to developing countries at high risk from climate change. Its main objectives include immediate emergency liquidity to alleviate the debt crisis, restore debt sustainability through disaster clauses and low interest restructuring, increased development lending and private sector investment, amended governance of international financial institutions to be more inclusive and equitable, and the creation of an international trade system that supports a global green and just transformation. This agenda has gained considerable momentum since its release in 2022, charting a course for the Paris Summit for a New Global Financing Pact in June of 2023 where the World Bank announced it would begin including disaster clauses in loan agreements.

The Accra-Marrakech agenda by Vulnerable Twenty (V-20) Group, which represents 58 nations, 1.5 billion people, and just 5% of global emissions, prioritizes debt management, transforming international financial systems, a new global carbon financing deal, and revolutionizing risk management.

African finance ministers also identified specific asks following the African Climate Summit that will help transform the system this year to do more for African countries. This includes re-channeling $650 billion SDRs to the African Development Bank, increasing IDA funding and accessibility, and overhauling the G-20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments due to the time intensive nature of this process.

Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery and Caribbean Emancipation 2030 represent other solutions being presented by civil society organizations to provide comprehensive debt relief and increase capital flows toward climate resiliency projects. The G-20 Capital Adequacy Frameworks Review offers suggestions from the Group of 20 to increase multilateral development bank lending capacity on better terms for member countries.

These reforms necessitate changes to the World Bank and IMF loan agreements, lending policies, and risk assessment methods. They also require the support of the institutions’ Board of Directors, who represent member countries’ interests. High-ranking leaders, including US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, have voiced support stating, “The international financial architecture is short-sighted, crisis-prone, and bears no relation to the economic reality of today.” Public praise for the Bridgetown Initiative has also come from Kristalina Georgieva, Managing Director of the IMF, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Director General of the World Trade Organization, French President Emmanuel Macron, and Bank of America Chief Executive, Brian Moynihan. New World Bank President, Ajay Banga has made the intersection of climate resilience and poverty reduction a clear priority as he faces pressure to deliver the $100 billion in new capital called for in the Bridgetown Agenda.

For more information on debt-climate crisis:

- How Are Climate And Debt Interconnected?, Eurodad

- An Urgent Plan To Avert The Debt Crisis, OneCampaign

- The Vicious Cycle: Connections Between The Debt Crisis And Climate Crisis, ActionAid

For more information on proposed solutions:

- Bridgetown Agenda, Bloomberg Green

- Accra-Marrakech Agenda, V20

- Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery

- Caribbean Emancipation 2030

- Reforming capital adequacy at MDBs: How to prudently unlock more financial resources to face the world’s development challenges, ODI

- IMF Lending Under the Resilience and Sustainability Trust: An Initial Assessment, Center For Global Development

- Innovative Financial Instruments for Climate Adaptation, International Institute for Sustainable Development