While respected as one of the world’s most important sources of energy data and analysis, the International Energy Agency has consistently underestimated the actual growth of renewable energy in their reports for at least a decade.

The IEA’s scenarios are widely used by governments and industry around the world for major energy investment decisions, and it will be relevant as the US government turns its sights to how it will deliver on its new 2030 emissions reduction goal and aims for a carbon-free power sector by 2035.

The agency’s special report on Net Zero by 2050 released in May 2021 offered some signs of a shift. The report made bullish projections about electrification, saying the entire power sector needs to be decarbonized by 2035 in the OECD and 2040 for non-OECD countries. It also concluded that countries around the world must end investment in new gas, oil, and coal if they are to achieve their net zero by 2050 climate goals.

However, the IEA’s flagship annual publication, the World Energy Outlook, has historically contained renewable energy growth projections that are far below estimates from other organizations, including Bloomberg New Energy Finance, and the International Renewable Energy Agency. In addition to the discrepancies in future scenarios, the IEA has regularly lagged behind reality in its past estimations of the rapid global rise in renewable electricity capacity.

Bad Track Record

A 2020 critical analysis from the Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney revealed a pattern of historical inaccuracies of the World Energy Outlook when it came to predicting growth of renewables and decline of coal. For instance, the analysis notes that the WEO projection for wind power by 2020 was reached 15 years early. The analysis also notes the IEA’s projection in 2002 for total solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity of 18 gigawatts was the same as installations made within just one year, 2007, five years later.

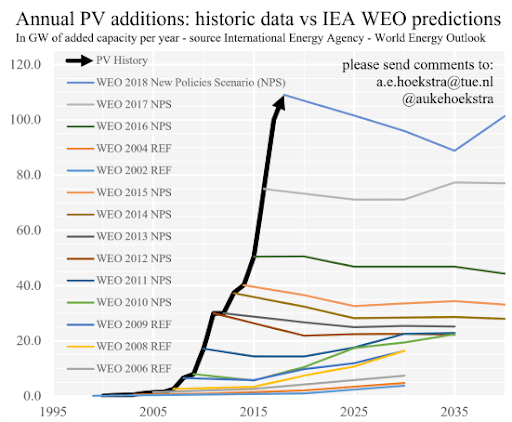

A report by the Energy Watch Group also points to errors in IEA’s basic assumptions about the growth of the renewable energy industry. The IEA’s World Energy Outlooks assume linear growth for solar and wind power, whereas these technologies have grown exponentially in the last decades and are expected to continue this pattern of growth for decades to come.

Since the 1990s, successive reports have projected linear growth for renewables for the foreseeable future. But even as the IEA ticked up its growth projections every year, the actual annual growth of the industry continued to exceed the predictions (see below):

(Source: https://maartensteinbuch.com/)

Other energy forecasters like Bloomberg New Energy Finances produce more likely estimates.

Though the IEA does have special reports devoted to clean energy, there has historically been concern that fossil fuel companies use the WEO’s optimistic projections to boost demand and artificially shore up investor confidence. As described below, there are signs this is starting to change. Fossil fuel companies have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo of steady growth in oil and coal consumption, and it appears that IEA models perpetuate that bias. The models incorrectly predict slow growth of renewables, and their consistent inaccuracy indicates that they do not factor in the rapid increase of private investment and domestic and international policy support for clean energy.

Business as usual for oil?

Several prominent forecasters, including BP, have started to project that global oil demand has already peaked or will soon. IEA however continues to expect oil demand will slowly grow and then remain steady after 2030.

The rate of electric vehicle adoption will have a significant impact on projected oil demand. Just as IEA underestimated renewable energy deployment for decades, by projecting steady oil demand it is effectively betting against continued cost declines for batteries.

Signs of Change

IEA’s 2020 World Energy Outlook for the first time included a net-zero emissions by 2050 “case” – a kind of cut-down scenario – in addition to its usual scenarios. The move followed repeated calls from a broad coalition of investors, businesses, climate leaders and scientists for the influential WEO to present a pathway aligned with the Paris Agreement goals. When the Outlook was released, IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol declared “solar is the new king of electricity.”

The IEA’s Net Zero by 2050 report released in May 2021 went further in putting forward for the first time a full-fledged scenario on aligning the energy sector with net-zero emissions by 2050 and the goals of the Paris Agreement.

However, although the IEA details strong renewables proliferation in the net-zero scenario, it sees growth in the sector decrease from 20 percent annual growth up to 2030 to just 3 percent a year in the decade after. Experts, such as those at Bloomberg New Energy Finance, disagree with this finding.

Some experts suggest that the IEA should partner with the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), an international think tank created specifically to analyze the development of renewable energy. IRENA’s research shows that scaling-up renewable energy combined with electrification could deliver more than three quarters of the energy-related emission reductions needed to meet global climate goals. While IEA’s World Energy Outlook and IRENA’s annual research offer somewhat different analyses of the future, both are international organizations with a mandate from governments to provide policy advice on how to speed up the world’s transformation to a low-carbon, clean energy system.

Developing Technologies

The IEA’s Net Zero by 2050 report finds that 50 percent of future emissions reductions will come from technology that is still under development. Almost all of the pathways in the IEA report to reach net-zero involve cutting emissions, but the report also includes a small but important role for carbon removal, which can close the gap to reach net-zero. Carbon removal is a technology to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and bury it underground. It is a tool to clean up carbon dioxide left in the atmosphere from earlier emissions and to counterbalance tough to decarbonize sectors. Carbon removal projects, such as Direct Air Capture technology, address in demonstration stages but are not yet available at commercial scale.

There are some examples in the report that conflate carbon removal with carbon capture. Maintaining a distinction matters because unlike carbon removal, carbon capture cannot reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the air. There are concerns that fossil fuel companies use carbon capture as greenwashing: maintaining the distinction between carbon capture and carbon removal is important and is something the IEA can provide more clarity on in future reports.

Carbon removal and emissions reductions are not an either/or proposition. While we must now supplement emissions reductions with carbon removal, carbon removal cannot replace emissions reductions. All known and proposed methods of carbon removal are too slow-acting, limited in scope, and/or expensive to entirely offset anything like society’s current carbon dioxide emissions.

What’s Next

IEA’s Net Zero by 2050 Report is designed to inform the negotiations that will take place at the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) of the United Nations Climate Change Framework Convention in Glasgow in November 2021. Several countries, including Australia and Japan, have already pushed back on the findings and indicated they will continue to invest in fossil fuels despite the report’s recommendations. IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol said the agency “is ready to help countries design their own national roadmaps – and to support the international coordination and cooperation that a successful global transition to net zero will require.”