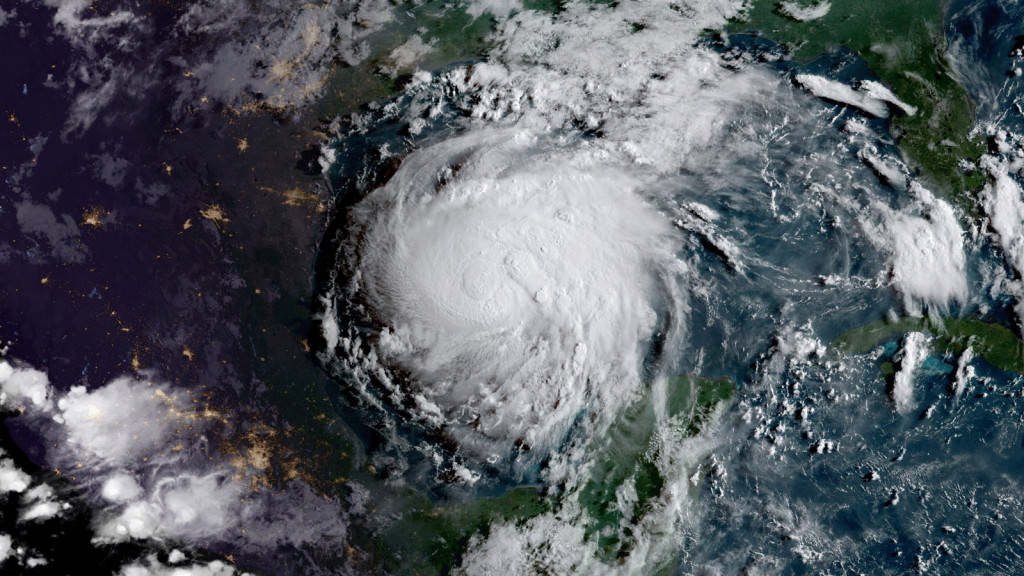

The science of attributing extreme weather to climate change is complicated and developing every day. Here’s a guide of what we know about the links between climate change and Harvey to help unpack the elements that contributed to this historic and unfolding storm. For a complete annotated backgrounder, visit the related events page on Climate Signals.

WARMTH

As seas warm, more water evaporates to the atmosphere. A warmer atmosphere can hold more water, fueling extreme rainfall and increasing flood risk. Record-breaking rainfall is a classic signature of climate change, and the fingerprint of climate change has been firmly identified in the observed global trend of increasing extreme precipitation.

- Many areas of Southeast Texas have received rain so extreme that historical data indicates it should only happen once every 1,000 years.

- Houston is experiencing its third ‘500-year’ flood in 3 years.

- Since the 1950s, Houston has seen a 167 percent increase in the frequency of the most intense downpours.

- A rain gauge in Mont Belvieu, about 40 miles east of Houston, registered 51.88 inchesof rain through late afternoon Tuesday. Once verified, this amount would break not only the Texas state rainfall record but also the record for the remaining Lower 48 states.

- A formal attribution study of last year’s historic flood in Louisiana found that climate change to date had most likely doubled the frequency of the extreme rainfall that drove that flood.

- Kevin Trenberth, a senior scientist at the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research, said, “The human contribution can be up to 30 percent or so of the total rainfall coming out of the storm.”

STALLED WEATHER

Another major contributor to the extreme rainfall totals was that Harvey stalled for many days over southeast Texas. Waves in the jet stream can stall in place (instead of moving eastward), leading to blocking and persistent weather patterns that fuel the intensity and duration of rainfall events.

- A study from March 2017 found that climate change is altering large scale weather patterns, such as the jet stream, which have the ability to dramatically amplify extreme weather events, such as extreme rainfall, during the summer.

- According to Michael Mann, the stalled weather pattern during Hurricane Harvey “is precisely the sort of pattern we expect because of climate change.”

SEA LEVEL RISE

Sea level rise has significantly extended the reach of storm surge and coastal flooding driven by hurricanes.

- While Harvey’s storm surge was not nearly as extreme as the observed rainfall, the twocombined to create what is known as “compound flooding.” Rivers rushing toward the Gulf coast met the storm surge coming inland and water “piled up from both sides”. In Galveston, the sea surge was about 3 feet but the actual water surge was about 9 feet due to compound flooding.

- A storm tide level of 7.0 feet above Mean Sea Level (MSL) was observed at Port Lavaca, Texas, during the storm—the highest storm surge in that location since Hurricane Carla in 1961.

ENERGY

The warmer the waters, the more energy available to passing storms, increasing the risk of major hurricane development. Climate change also affects other factors that shape and control hurricane development, such as wind shear. The balance of all these factors is not fully known. However, hurricanes have grown stronger over recent decades. And there is a significant risk global warming may be driving that trend.

- Harvey rapidly intensified from a regenerated tropical depression into a Category 4 hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico, aided by sea surface temperatures up to 2.7 – 7.2°F (1.5 – 4°C) above average.

- Last winter, the daily surface temperature of the Gulf of Mexico never dropped below 73°F for the first time on record.

RAPID INTENSIFICATION

There is an observable trend toward increasingly rapid intensification of hurricanes, leaving less time to prepare. There is a significant risk that this trend is driven by global warming.

- Harvey’s rapid intensification is consistent with the observed trend toward rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones, particularly in the North Atlantic and Caribbean.

FAQ – Tropical Storm Harvey Climate Change Fingerprints

What about natural variability?

Climate change often magnifies the scope or frequency of a disaster, while natural variation is often the dominant determinant for an event’s occurrence and overall activity. However, the more extreme the event, the larger the likely contribution of climate change to the event. In this case, unusually warm waters and atmosphere supercharged the storm, contributing to the record-breaking rainfall.

What role does sea level rise play?

Sea level rise attributable to climate change is more than half a foot over the past few decades. That means that the storm surge was a half foot higher than it would have been just decades ago, resulting in far more flooding and destruction.

Does “uncertainty” mean scientists don’t have enough evidence to confidently point to the climate connection?

It’s important to keep in mind that any time scientists in any field collect data on any subject there is uncertainty. Uncertainty refers to the fact that you can never really measure anything exactly. The existence of uncertainty is by no means a disqualifier for scientists to speak with confidence as long as they address the range of uncertainty. There are degrees of uncertainty, but some things we can say for sure: seas are rising and amplifying storm surge, climate change fuels extreme rainfall and is increasing the potential energy available to passing storms.

Hasn’t there been a major US landfalling hurricane drought? And isn’t this an anomaly?

The argument that, before Harvey, it had been many years since the US experienced a major hurricane is sophisticated cherry picking. Each qualifier before the word drought—landfalling and US landfalling—makes faulty assumptions that obscure the overall picture of changes occurring in the Atlantic hurricane basin. A frequency analysis published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society established that this data cherry picking is responsible for the illusion of a “drought” in landfalling hurricanes in the US. One needs to look at multiple decades to identify changes in the frequency of major landfalling hurricanes. Such data does show that there has been an increase in the Atlantic basin as a whole.

Is this a “taste of things to come?”

We are living with the reality of climate change, right here and right now. Since 1850, the planet has warmed significantly and the toll can be seen worldwide. In the US, the impact of climate change in is now clear, costly and widespread.

Why is it important to talk about climate change now?

In a warming world, talking about an extreme weather event without discussing how climate change exacerbates the destruction and the suffering does not provide a complete picture. Including the context of climate change enables decision-makers to prepare for future impacts and empowers citizens to hold their elected leaders accountable to addressing the root problem. The underlying reason for the uncertainty around talking about climate change is because the fossil fuel industry deliberately obscured this reality from the public for decades, and has a vested interest in limiting knowledge around the damage that their products cause. Muting discussion on climate change as a devastating storm unfolds is a political strategy that serves the interests of those who wish to delay meaningful action on climate change.